Herstory of the City, Part III

When the original Hannibal Bridge was completed in 1869, it established Kansas City as the dominant regional power. The current Hannibal Bridge (pictured) was erected in 1917.

Published March 16, 2022

A NOTE FROM THE WRITER: When I started disKCovery, it was not only about sharing my own journey to discovering Kansas City, but a way to push myself to continue being a tourist in this city that I am proud to call home. While that journey is largely about the Kansas City we know now, it can be difficult to understand and truly love a city without understanding the context of what we see today. So for this month, Women’s History Month, I am going to step away from my usual programming and share a series of essays that explore some of the kick-ass ladies who helped shape our city, our region, and the world. If you have not already done so, I encourage you to click HERE and begin with “Herstory of the City, Part I”.

There are a few reasons that writers write. As for me, this month, I am going to share the stories of some incredible Kansas City women. Whether or not you are entertained, persuaded, or informed; well my friend, that is up to you.

Part 3: Takin’ Care of Business

One fact that every Kansas Citian seems to inherently know is that KC has more boulevards than almost every city in the world, second only to Paris, France. The universal awareness of this statistic leads many to believe it is the cause of a civic nickname which is similarly a part of the Kansas City zeitgeist, “The Paris of the Plains”. Interestingly, one is not related even slightly to the other.

The famed nickname was actually embraced by Kansas Citians in the 1920s after Edward Murrow wrote in the Omaha Herald, “If you want to see some sin, forget Paris and head to Kansas City.” This was a clear reference to Kansas City’s status as an “open city” where law enforcement stood idly by as hedonism ran rampant.

“If you want to see some sin, forget Paris and head to Kansas City.”

There is perhaps no figure in the city’s history more romanticized than “Boss Tom” Pendergast. His general disregard for the rule of law (particularly as it pertained to prohibition and gambling), his corrupt political machine, and alliances with organized crime syndicates that made Kansas City a center of commercialized vice, are the stuff of local legend. What many in Kansas City fail to realize is that Pendergast’s reign was only the final chapter of a salacious and sordid tradition that was embedded in this city’s bedrock from the time of incorporation. Decades before Las Vegas was ever even dreamed of, this was Sin City.

The Town of Kansas (as Kansas City was originally known) was first and foremost a river town. It grew up along the banks of the Missouri River in the neighborhoods we now know as the West Bottoms and the River Market. When the Hannibal Bridge was opened in 1869, bringing the railroad across the river into the River Market, it immediately established Kansas (City) as the dominant regional power.

Today, the River Market is known for loft-style living, its collection of bars and restaurants, and the weekend flea and farmers’ markets at the City Market. Established in 1857, City Market is considered to be Kansas City’s oldest continually-operating business. But, did you know that for the better part of 60 years, this city’s oldest business was surrounded by the world’s oldest profession? From Kansas City’s infancy, the charming neighborhood that we know now was actually our city’s Red Light District.

Long before Pendergast would make his mark on KC, this area was home to over 40 brothels, as well as dozens of saloons, billiards halls, bars, and gambling dens. It was this proliferation of decadence that made Kansas City “The Paris of the Plains”. And it was in that Kansas City, that this city’s first self-made female entrepreneur, Annie Chambers, flourished.

Kansas City’s Madame

Annie Chambers (1842 - 1935)

Annie Chambers may not be a woman whose name you expect to see on a roster of this city’s greatest female icons. And yet, this is exactly where she belongs. The tale of Annie Chambers is one of determination. It is the story of a woman who made the most of several awful situations and found a way to come out better on the other side. In the process, she left an indelible mark on this city and its people.

Annie Chambers was born Leannah Loveall in Kentucky in 1842. As a young woman, she was cast out by her Dixiecrat father after she “borrowed” his horse to participate in a local parade honoring Abraham Lincoln, who was campaigning in nearby Lexington for the 1860 Presidential election. After being estranged from her immediate family, Annie went to live with an aunt and became a schoolteacher.

Around the time she turned 20, Annie met a railroad man who was twice her age, named William Chambers, and the two were wed. Shortly thereafter, Annie became pregnant but the couple lost their first child due to miscarriage. While Annie was pregnant with her second child, she and William were in a carriage accident. Being thrown from the buggy put Annie into a three-day coma. When she awoke she found that her second child had been stillborn while she slept, and that William had been killed in the accident.

Overcome with grief and seeing no life for herself in Kentucky, Chambers followed a friend to Indianapolis. In the wake of her losses, she could not bring herself to return to teaching and be surrounded by children. There were very few job prospects for women in a society where women were wholly dependent on their husbands or fathers for support. Having been through so much tragedy, Chambers believed that her life was not going to last much longer anyhow. So she and her friend turned to a life of prostituiton to support themselves. It was with this move that the former Leannah Loveall Chambers began working under the name “Annie Chambers”.

“I believed everything was against me. I decided to go to Indianapolis and have a short but fast life, and a merry one.”

Sadly, for Annie Chambers, life did not get any easier in Indiana. Prostitution was frowned upon in Indianapolis and constant police raids made it difficult for her and her friends to work. To compound things, Annie fell in love with one of her customers. The two got engaged only for Chambers to learn that her new fiance was married and had a family. As the 1860s came to a close, the 27 year old widow was ready for another change of scenery. A fellow prostitute who had recently returned from a certain Midwest river town, suggested that she knew of a city that might be the perfect place for Chambers to start fresh.

When Annie Chambers arrived in Kansas City in 1869, it was in the midst of a population boom. What had once been a small trading outpost, had grown in population from 6,000 people to over 30,000 in the five years before Annie arrived. The recent completion of the (first) Hannibal Bridge promised to add to that growth as now the rail had been brought over the Missouri River and into Kansas City. Combined with its location on the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers which boasted a lucrative riverboat trade, the arrival of the rail made Kansas City the undisputed center of commerce in the region.

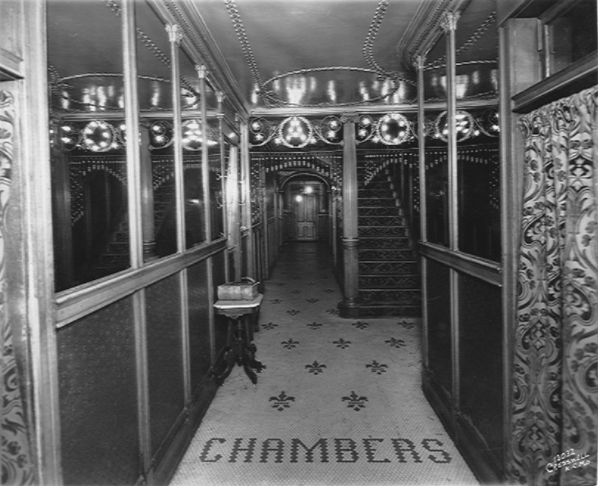

Annie Chambers’ “resort” was the crown jewel of Kansas City’s Red Light District for nearly 50 years. IMAGE COURTESY OF: Missouri Valley Special Collections

The newly established stockyards in the West Bottoms were shipping beef out east and the newly built grain mill was sending flour right along with it. Westward settlers were coming to Westport and Independence to get their supplies before making their way across the plains. This was a city where a lot of money was coming in. This was a city where hundreds of people, most notably unmarried men, were arriving daily via the river and rail. The number of men in the city largely outnumbered the women in those first couple of decades. And most importantly, Kansas City was a city without an organized police force. All of these factors made this booming river town a veritable land of opportunity for Annie Chambers.

Within a year of moving to Kansas City, Annie Chambers established her first brothel on the north side of the river in the neighborhood we now know as Harlem. Two years later, in 1872, she moved across the Hannibal Bridge into the heart of what was quickly becoming the city’s Red Light District. Chambers borrowed $100,000 (which she would end up paying off in two years’ time) to build a 25-room mansion at the corner of Third and Wyandotte.

Chambers’ bordello, or as she referred to it, her “Resort”, immediately set itself apart from the nearly 50 other brothels in the area. No one had ever seen a anything quite like it. The floors in the entryway were laid with marble tile. Wall-to-wall carpet and immaculate wallpaper enveloped the bedrooms. Beautiful chandeliers hung from the ceilings. Leather and velvet furniture was found throughout the common areas. The walls were adorned with European paintings and antiques. In an ocean of River Market whorehouses, Chambers’ resort was a palace!

Annie Chambers built her mansion with higher-end clientele in mind. A woman with a sharp business mind, Annie believed that by building a brothel that mirrored a luxury hotel, it would give her business the credibility it needed to provide a luxury experience that customers would pay a premium for. As it turns out, she was right.

While “accommodation” could easily be found across the Red Light District for as low as 25 cents, the women employed by Chambers were charging $10 or more. Beyond bedroom extracurriculars, Chambers also sold fine wines and cigars to the resort’s clientele. At five dollars a bottle, the sale of wine often brought in more than the prostitution. She brought in other forms of entertainment that kept guests at the mansion and spending money such as burlesque, performers, and gambling.

And in turn, her business model attracted rich and powerful men. There was no shortage of customers or demand for Chambers’ brand of prostitution. While everything about Chambers’ brothel was meant to feel and seem exclusive, the doors of the resort were open to any man who wished to enter, provided he could afford it.

In 1874, Kansas City established its first police force. In 1880, the city enacted its first “sin laws” against behaviors such as prostitution. But by then, Chambers’ mansion at 201 West 3rd Street was an institution. Even though she was only a few blocks from police headquarters, her brothel was never raided. The resort was in the shadow of the City Hall but, for those first thirty plus years, it was never shut down. The worst that ever happened was that Chambers would have to pay a “sin tax” of $20 to $30. Legend has it that Chambers was quite efficient at greasing the wheels of City Hall and local law enforcement. While likely true, the lack of pressure from the city was more a reflection of the fact that it was not just visitors to Kansas City who were frequenting the resort. Chambers’ best customers were locals, and many of them were among the city’s elite.

A rare look inside Annie Chambers’ bordello at 3rd Street & Wyandotte. ORIGINAL PHOTO SOURCE UNKNOWN

Much like today, the business of prostitution was one where women were often mistreated and taken advantage of. By all accounts, this does not seem to have been the case with Chambers and the women she employed. She prided herself on providing an avenue for young, single women to support themselves and make a living because she knew firsthand what it was to be in their shoes. She did not see the women she employed as employees or even sex workers, she saw them as kindred spirits and felt a duty to provide them with the tools to control their own fate.

The women who worked for Chambers were the best paid female employees in the city. Sex workers in Chambers’ brothel kept 50% of the money from each accommodation. This was virtually unheard of in the district. This means that many of the ladies who Chambers employed were taking home at least $100 per week (Over $2,500 by today’s standards).

Chambers never lost her ability to be a teacher or her desire to be a mother. She taught her employees social skills, manners, and etiquette. She educated them in academic and financial matters. Not only did having prostitutes who could communicate with higher-end clients make Chambers’ brothel very profitable, but she was always preparing the women she employed for a life after her resort.

Chambers dressed the women who worked for her in the latest fashions. In fact, it was said that Chambers was the largest buyer of clothing from Emery, Bird, and Thayer - one of the city’s most reputable clothing stores. She prohibited lewd behavior outside the bedroom. The women who worked for her were restricted from getting drunk, smoking, or swearing in public. They were expected to be fully dressed in the resort’s common areas and even their forearms were not allowed to be exposed. Once again, the ambiance of dignity helped to give Chambers’ brothel the high-class feel that made it so successful. But, more importantly, Chambers’ was making sure that the women she employed were seen as marriage material. While Chambers had made prostitution her life, she saw it as a means to an end for women who needed her help.

Later in life, Annie Chambers would brag about all the women she helped find good husbands of means. She would talk about how many women she helped start their own families and break their own cycles of personal tragedy. In many of these instances, these couples met within the walls of Annie’s resort. She took pride in the many women that she helped get out of the profession and break their own cycles of personal tragedy.

In the 1910s, the Temperance Movement, which had been championed by Belton, Missouri and Leavenworth, Kansas native Carrie Nation, was gaining momentum. The United States was on a collision course with Prohibition. As public opinion began to rise in opposition to alcohol, the Temperance Movement also led to a shift in public sentiment towards other forms of “commercialized vice” as well.

Throughout the 1910s, organizations that existed for the sole purpose of challenging saloons, gambling dens, and brothels were effective in shutting down a number of these businesses in Kansas City. And yet, they almost had no impact on Chambers’ resort, in spite of it being their primary and most visible target. When Chambers’ resort was raided, police found nothing to charge her for. When injunctions were filed that shut down Chambers’ brothel, city judges threw them out in court. Kansas City’s Madame seemingly wielded a lot of influence at City Hall.

Ultimately, Chambers was forced to shut down her brothel. So much of her business was tied to the sale of alcohol and the onset of Prohibition limited her ability to run her resort as she once had. After nearly fifty years at the helm of the crown jewel of Kansas City’s Red Light District, Annie Chambers went legit and closed her business in 1921.

As the neighborhood around her changed, Chambers did what she had always done - she adapted. Still wanting to provide accommodation, albeit a different kind, to the abandoned women and wayward travelers of Kansas City, Chambers re-opened her mansion as a boarding house. In the late 1920s, Chambers capitalized on the public intrigue that surrounded her mansion by offering tours of the former bordello. Chambers would regale paying customers with a half century’s worth of stories from running Kansas City’s most notorious brothel.

Near the end of her life, Annie Chambers was befriended by the most unlikely of neighbors - Reverend David Bulkey and his wife, Beulah. After hearing Reverend Bulkey eulogize the funeral of a call girl’s deceased infant, Chambers was so moved that she converted to Christianity. While she would spend the remainder of her days speaking out on the evils of prostitution, she never publicly expressed regret for having participated in the trade or denounced her own involvement. She was proud of the life she created for herself. More than anything, whether it was by employing them in her brothel or through her boarding house venture, she was proud of all the women she had given a fresh start and helped to get their lives on track.

In 1935, Annie Chambers passed away in the master bedroom of the $100,000 house that she had built on the corner of Third and Wyandotte. It is said that her funeral was attended by a cross-section of Kansas City, with people in all forms of dress, from all walks of life. Common folk were seated next to the city’s elite. After all, many of Chambers’ clients were likely men whose names are now immortalized in this city’s streets, parks, and fountains.

Most notable among the swarms of people who attended her funeral though was the conspicuous multitude of affluent, fashionable women who appeared to be among the social elite. These were clearly the women who Chambers had employed who were appreciative of all she had done for them. Of course, Reverend Bulkey, the man whose funeral sermons helped Chambers to find religion so late in life, eulogized her service.

In her Last Will and Testament, Chambers left the 25-room resort to the Bulkeys and City Union Mission. For the next decade (until it had to be torn down for structural reasons), the house that Annie Chambers built continued to do what it had always done in its own way - it welcomed and provided aid for the displaced women of Kansas City.

So, What Do I Do Now? Take a walk around the River Market and think about the neighborhood that this once was. Go stand where Annie Chambers’ famed resort once stood at 201 West 3rd Street. It is now home to the River Market’s famed A Tribute to the Journey of Discovery mural which details the expedition of Lewis and Clark. If you really want to go back in time correctly, Voice Map offers an incredible free walking tour of the River Market about Annie Chambers that you can download, free of charge, and listen to on your phone as you walk the neighborhood that once was Kansas City’s Red Light District.

Today, the corner of 3rd Street and Wyandotte is home to this famed mural of the Lewis and Clark expedition but at the height of Kansas City’s Red Light District, this was the site of Annie Chambers’ bordello.

Kansas City’s Clothier

Nell Donnelly Reed (1889 - 1991)

As Kansas City’s Red Light District, and by extension Annie Chambers and her bordello, endured their twilight, Kansas City’s first (legitimate) self-made woman was just getting started. Like Chambers, Nell Donnelly Reed had a strong business acumen, recognized a niche in the market that needed to be filled, and was highly successful because she had the determination to bring her designs to fruition. She also employed a largely female workforce (though in a more legitimate manner) and cared about the people she employed. However, that’s where the similarities between these two entrepreneurs end. While Chambers operated in an unsavory trade within the shadows, the woman that many would soon know as Nelly Don was thrust into the limelight as her innovations helped to establish what has become a multi-billion dollar industry.

Nell Donnelly Reed was born Ellen Quinlan on March 6, 1889 in Parsons, Kansas to Irish Catholic immigrants. The fifth and youngest daughter in a family of thirteen children, Ellen, or Nell, was the constant recipient of hand-me-downs from her older sisters. Like many women of the period, Nell’s mother taught her how to sew from a young age; but Nell showed a particular talent with the needle and thread. Her proficiency as a seamstress proved useful as Nell was not only able to mend the heavily used and worn clothing she was expected to wear. She frequently was able to repurpose and refashion several of these garments to create designs that she could be proud to don.

From a young age, Nell Donnelly Reed showed an aptitude with the needle and thread that allowed her to convert hand-me-downs into fashionable garments. PHOTO COURTESY OF: Missouri State Historical Society

At the age of 16, Nell moved to Kansas City and took up residence in a boarding house while working as a court stenographer. It was here that she met fellow stenographer, Paul Donnelly. The two were wed a year later when Nell was only 17 and Paul was 23. As someone who had always valued her own education, Nell enrolled at Lindenwood College shortly after getting married. A married woman choosing to attend college was unheard of during that era. In fact, Nell Donnelly was the only married woman in any of her classes! Paul supported her decision entirely and after Nell completed her degree in 1909, the pair returned to Kansas City where she initially assumed the role of a homemaker.

In the 1910s, women’s fashion was incredibly limited. For those who could afford it, tailors who could custom-make and fit clothing were plentiful. However, few were wealthy enough to procure their services. There were a number of pre-made fashions available but they were too expensive for working-class women and were redundant to those who could afford pre-made fashion because they could also afford the much more favorable route of a tailor. For the average woman, the only pre-made rack dresses available were cheaply-made, shapeless, lifeless, and unflattering. The realities of women’s fashion in that era led Nell Donnelly to tap into her talent as a seamstress and do what she had always done: take the clothes available to her and re-fashion them into designs that she was proud to wear.

Soon enough, her friends took notice. That envy allowed Nell Donnelly to clearly see there was an underserved niche in fashion: working class women who desired to have clothing that was functional, form-fitting, and attractive. While Donnelly’s friends loved her dresses, store owners were not as receptive. Many times, male shopkeepers did not recognize the same gap in women’s fashion that Nell did. They did not see the difference between what they were already selling and what Nell was offering. Additionally, with house dresses selling for 69 cents in most stores, many store owners thought it foolish to even try and sell Nell’s $1 dresses.

Nell was confident that women would respond to her dresses, but no one was willing to sell them. She soon realized that her only course of action was to try and sell her dresses on consignment. That is to say, she would assume all the risk as the store owner would not have to pay her for her dresses until they had sold. Under this model, Nell was able to convince George Peck to place an order for eighteen dozen of her dresses to sell in his store. Paul invested the couple’s savings into several foot-pump sewing machines and Nell enlisted a few friends, neighbors, and family members to help. They were able to fill the order in two months’ time.

On the very first morning they were available in 1916, George Peck’s Dry Goods Store sold out of all 216 “Nelly Don” dresses before noon!

Around this time, Paul was called away to serve this country in World War I. However, before he left, he opened a line of credit for Nell and secured factory space in the Coca-Cola Building (or as you may know it, the Western Auto Building). In turn, Nell hired eighteen women and got to work. Right away, she saw the same kind of demand for her dresses that Peck’s initial run had created.

What made the so-called “Nelly Don” dresses so special was their unique combination of practicality, style, fit, and quality. Donnelly made her dresses in such a way that, much like her younger self, her customers could easily make repairs and alterations without requiring the services of a hired seamstress. Being a size 16, and having struggled to find dresses in stores that she both liked and fit properly, Donnelly made it a priority to make a product that catered to women of all shapes and sizes and was still affordable.

Early on in her foray into dress-making, Nell discovered that, much like Henry Ford’s famed assembly line, by putting different workers in charge of creating different parts of each dress, she could drastically increase the rate of production without sacrificing one bit of quality. Her implementation of this process was one of the many ways that helped to keep her dresses affordable.

By the time Paul returned from Europe in 1918, Nell’s operation had over $250,000.00 (nearly $5,000,000.00 by today’s standards) in sales and not a cent of debt. Nell was the second self-made female millionaire in United States’ history.

In 1919, Nell and Paul officially founded the Donnelly Garment Company. As the company grew, demand grew right along with it.

Nell Donnelly always had an eye for the latest trends. She constantly mimicked the top styles and fashions of the time. In the early 1920s, inspired by the growing popularity of French silk, she took the same beautiful patterns that European fabrics were renowned for and had them printed on linen. This allowed her dresses to not only be beautiful and stay affordable, but of the utmost importance - it allowed Nell’s dresses to be easily washable. By 1923, Donnelly was employing over 250 people in her factory.

As the Great Depression came, and dress sales began to plummet, the Donnelly Garment Company adapted by focusing on the production of aprons. Nell’s “Handy Dandy Apron” was a hit. From a customer’s perspective, the apron was practical, fit well, and had plenty of pockets. And yet, it was still stylish and form-fitting. From the Donnelly Garment Company’s perspective, it was easy to produce. Because of Nell’s patented single-seam design for the apron, that meant a Handy Dandy Apron could be made from start to finish in a single motion. As the 1930s began, the Donnelly Garment Company had moved their operation to Corrigan Station. They had over 1,000 employees and were doing millions in dress and apron sales every year.

As the “Nelly Don” brand grew, Nell Donnelly became not only a Kansas City icon, but a national one as well. At this time, it’s estimated that 1 in 7 women in America owned a Nelly Don dress. In 1931, Paul and Nell moved into the famed Tureman Mansion in Crestwood. As Nell found even greater success, the attention she received as a result was not always favorable.

In the winter of 1931, Nell Donnelly and her chauffeur George Blair were abducted in front of the Tureman Mansion. The kidnappers threatened to maim Nell and murder Blair if Paul Donnelly did not pay the $75,000 ransom they were demanding. Given the prominence of Nell Donnelly, the story was quickly sensationalized and captured headlines across the nation.

In 1931, Nell Donnelly made national headlines after she was kidnapped in front of the Tureman Mansion, where she lived with her husband Paul.

To help find Nell, Paul enlisted the help of neighbor, James A. Reed. With the backing of the Pendergast political machine, James A. Reed served as Mayor of Kansas City before being elected to the United States Senate three times, and was even a Democratic Presidential candidate in 1928. After failing to secure the nomination, he retired to Kansas City. At the time of Nell’s kidnapping, Reed was living next door to the Donnellys and practicing law.

Reed used his connections and convinced Kansas City, and Pendergast-connected, mobster Johnny Lazia and his crew to orchestrate their own search for Nell Donnelly, in addition to the one being conducted by the Kansas City Police. Within two days, Lazia and his goons found Donnelly and Blair in a farmhouse in Bonner Springs, Kansas. They were returned safely home without any ransom having been paid. The kidnappers fled, but were ultimately tried and convicted.

The following year, Nell Donnelly divorced Paul and bought out his share of the company for $1,000,000.00. While it was not known at the time, Paul was manic-depressive and his undiagnosed chemical imbalances had caused him to become physically and emotionally abusive towards Nell. He reportedly even threatened her at gunpoint over the prospect of having children and starting a family. Paul was also an alcoholic and a philanderer who was unfaithful to Nell. Although in that final regard, Nell was not entirely innocent. The story on Nell’s only son, David Quinlan, who was born in 1931, was that he had been adopted while Nell was on tour in Europe. In fact, he was actually fathered by the next-door neighbor who had been so eager to get Nell safely home, Senator James A. Reed.

Nell and Senator Reed were wed in 1933. Senator Reed subsequently adopted his own biological son and David Quinlan became David Quinlan Reed. Unlike Paul, Reed would never have any involvement in the Donnelly Garment Company. Sadly, Paul, having squandered his wealth and suffering from manic-depression, committed suicide in a Connecticut sanitarium in 1934.

Aside from the implementation of the assembly line and her innovative garment designs, Nell Donnelly Reed was so successful because of the revolutionary way she treated her employees. She reportedly paid her employees some of the highest wages being offered to factory workers anywhere in Kansas City. She had a cafeteria, medical clinic, and recreation center on-site for her employees. She established a pension plan for them and gave them life insurance. She offered to cover the tuition of any Donnelly Garment Company employees who wanted to attend college at night. Always a proponent for education, Nell even established a scholarship fund for the children of employees. Her factory was one of the first ever to be air-conditioned.

Her employees were so seemingly happy that when the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (IGLWU) attempted to unionize the Donnelly Garment Company, her employees responded by rejecting the union and starting the Nelly Don Loyalty League.

An exhibit highlighting some of the famed Nelly Don dresses. PHOTO COURTESY OF: University of Missouri

It must be stated that there are some conflicting reports regarding Nell’s treatment of employees. There were allegations that the employees of Donnelly Garment Company were actually overworked and underpaid. Additionally, Donnelly was accused of utilizing the assembly line approach so that she could categorize her employees as “unskilled labor” and pay them less.

While these allegations still persist, they seem to be unfounded rumors that are remnants of an era where Nell Donnelly clashed with the IGLWU. What everyone agrees on is that Nell Donnelly Reed was not a fan of unions. In fact, it was not until 1968, long after Nell retired, that the employees of the Donnelly Garment Company would join the IGLWU.

During World War II, Nell Donnelly Reed turned her attention to the war effort as her company made military and medical uniforms for men and women. It is estimated that Donnelly Garment Company made over 5,000,000 pairs of underwear for the United States Military. And she sold every single garment for the military to the United States Government at cost. She reportedly did not profit at all from the war effort.

“By 1935, Nell Donnelly Reed was described by ‘Fortune’ magazine as possible the most successful businesswoman in the United States.”

After the war, Reed built the largest dress-making factory in the world on Kansas City’s Eastside. It covered two city blocks and had its own train depot! At that time, the Donnelly Garment Company was doing $14,000,000.00 in annual sales. When Nell retired from the company in 1956, she was considered the largest dress-maker in the world.

In 1958 the company went public as Nelly Don, Inc. Under new ownership, the company went bankrupt in 1978 due largely to the demise of Kansas City’s Garment District and the outsourcing of garment production overseas. Just as a desire for cheaper production had brought the fashion industry to Kansas City overnight, it seemingly left just as quickly sixty years later for the same reasons.

Nell Donnelly Reed enjoyed hunting and fishing, an interest she had acquired from her husband, Senator James A. Reed. He was an avid outdoorsman. It was said that after marrying Reed, Nell never missed an opening day of hunting season. After Reed passed in 1944, Nell donated a plot of land near Lee’s Summit back to Jackson County. This became the James A. Reed Memorial Wildlife Area.

In retirement, aside from hunting, Nell Donnelly Reed turned to a life of philanthropy giving her time and money to a number of local community organizations. She passed away at the age of 102 in 1991 and was interred in Independence, Missouri.

So, What Do I Do Now? Nell Donnelly Reed’s story is all around us. She put the area that we now know as the Garment District on the map. Her factories occupied the Western Auto Building and Corrigan Station. Perhaps, the best thing to do is to visit the Tureman Mansion. This beautiful estate was Nell and Paul Donnelly’s home during her famed kidnapping in 1931. Today, the mansion is open to the public as it houses The National Museum of Toys and Miniatures.

The land for the James A. Reed Memorial Wildlife Area, near Lee’s Summit, Missouri, was donated to Jackson County by Nell Donnelly Reed after Senator Reed’s death.

The contributions of entrepreneurial women in Kansas City are, by no stretch of the imagination, limited to Annie Chambers and Nell Donnelly Reed. You may recall that Nelle Peters and her architecture firm were previously discussed in Part I of Herstory of the City.

For the better part of 40 years, Hazelle Hedges Rollins’ factory in the Garment District was the largest exclusive manufacturer of puppets and marionettes in the world! Many of the puppet materials that Rollins developed and the mechanisms that she invented for marionettes are still in use today. Sarah Rector was a black member of the Muscogee Nation. When she was 12, Standard Oil Company struck an oil gusher on a parcel of land that had been bequeathed to her in Oklahoma. By the time Rector moved to Kansas City, Missouri in 1920 at the age of 18, she was already a millionaire and considered the richest black woman in the world.

Around the same time that Reed was launching her fashion empire, Clara Stover and her husband Russell, famously co-founded Russell Stover Chocolates. Clara Stover was not only a co-founder, and President of the company after her husband Russell’s death; she branded the company’s greatest innovation. When Russell and another chemist patented a process for coating ice cream in candied chocolate without melting the ice cream, it was Clara Stover who named the creation “the Eskimo Pie”. A national sensation was born. The Eskimo Pie was the springboard that vaulted Russell Stover from a small candy outfit to the nationally recognized household name that they are today.

In more recent history, Kansas City gave birth to another major fashion icon, Kate Brosnahan. Or, as you more likely know her, Kate Spade. Spade created a line of handbags and purses that fused together practicality with style and flair at a price point where people could afford to own multiple bags from her collections. Sounds similar to another Kansas City fashion icon, does it not?

A last-minute decision to move her “Kate Spade” label to the exterior of the bags was a homerun as people took notice of the brand. An overnight sensation in New York City in the 1990s, Kate Spade grew into a global fashion empire with a catalog that eventually expanded to include apparel for men and women, as well as housewares.

And these are just a handful of the stories. The song of this city was crafted by self-made, independent women, who had the vision to recognize a marketplace need and then had the audacity to actually respond to it. Even today, this proud tradition continues as Kansas City remains a hotbed of entrepreneurial activity; with several women at the forefront. There can be no doubt, that much like the two centuries before it, the 21st century in Kansas City will be heavily influenced and driven by innovative women.

Join me next week, as we continue of exploration of Kansas City’s herstory and the amazing women who made our city what it is today.

Subscribe to disKCovery to be the first to know when “Herstory of the City, Part IV” drops.

Have a favorite icon of Kansas City herstory? Or maybe a fun fact or tidbit about Annie Chambers or Nell Donnelly Reed? Let me hear it in the comments!

Many thanks to my mother, Janell Dignan, for proofreading and editing these stories. I would not have pulled off this series without you!